I’ve been on a bit of a schools/teaching kick lately with this blog, which has been fun (if you want to see more bird pics, check back starting April 8!). My reflections on “good teaching” bring me back to one of the things that inspired the teaching component of my Big Year: my trip to Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire three years ago. It was an amazing trip, and gave me so much to think about. I wrote up an informal report of my trip for some of my Lakeside colleagues, and I have decided to reprint that report here. Just to be clear, I did not visit Exeter again – this is from three years ago. In that time, the concept of the “flipped classroom” has really gained popularity – and it’s interesting to compare “the flip” circa 2013 with what Exeter has been doing for decades. Finally, this report was written for a Lakeside audience, so phrases like “the way we do things here” mean the way we do them at Lakeside. Enjoy!

Caryn Abrey and I visited Exeter in April of 2010, and spent almost two days touring the school, observing classes, and talking to adults and students. We were struck by a whole range of differences between Exeter and Lakeside, but three things that made a particular impact on us were Exeter’s approach to science teaching (the Harkness Method), their use of a weekly Meditation period, and their process of initial teacher evaluation and induction.

Harkness Method in Teaching Science

One of the things for which Exeter is famous is the Harkness method of teaching, in which small classes of students sit around an oval table with the instructor. It is a “student centered classroom” in which the teacher does not lecture or directly control the discussion. Students take primary responsibility for driving the lesson forward, asking and answering each others’ questions, and constructing their own understanding of the topic. Teachers may sometimes step in to ask questions, redirect errant discussions, or provide some clarification, but they do not dictate the pacing, interpersonal dynamics, or (sometimes) even exact content of the lesson.

While Exeter has been using the Harkness method since the 1930s, I was surprised to learn that science classes did not employ this method until the early to mid 1990s. At that time, the science faculty were, in fact, the lone hold-outs in keeping lecture as their primary mode of instruction. In the 1990s, some of the science teachers began to experiment with a more student-centered approach. Progress towards a “science Harkness method” was somewhat gradual and inconsistent at first, but momentum began to build as the science faculty started planning their impressive new Phelps Science Center. One of the questions that the Exeter science teachers wrestled with was whether to include space in each new science classroom for a Harkness table. At first they were significantly divided on this issue, but finally reached consensus: the science dept would embrace Harkness as the standard mode of instruction for all science classes, starting with the completion of the Phelps Science Center in 2001.

Phelps Science Center

While all of the science teachers agreed to use the Harkness method in their classes, there is no single definition for what Harkness is. The key elements seem to be a student-centered classroom in which the students take primary responsibility for their own learning. The teacher can act as a support or guide in this process. Within the department, there is apparently a spectrum of how student-centered each class is, with different teachers interpreting for themselves the right balance of student-teacher voice and influence. There is no official “enforcer” of “Harkness orthodoxy” on campus (or in the dept), and teachers are actually given a little freedom in finding a precise Harkness style that works for them. However most of the adults we talked to were very clear about the distinction between the Harkness method (endorsed and used at Exeter) and the Socratic method of teacher posing questions to students (not really promoted by Exeter). While in real life these two techniques share some similarities, Exeter faculty explained that the Socratic method, while fostering student involvement and dialogue with the teacher, is still ultimately an expression of a teacher-centered classroom. In a Socratic classroom, much of the conversation is teacher-student-teacher-student-teacher-student (represented by spokes on a wheel with the teacher at its center), while a Harkness classroom is much more likely to be teacher-student-student-student-teacher-student-student. In fact, for a while in several classrooms, the teacher seemed almost invisible or irrelevant for parts of the lesson.

A Chemistry Classroom with Harkness Table

While I had a basic idea of the Harkness method before I visited Exeter, I had a very hard time envisioning how this approach could be successful in science. Without lecture, how would students learn any content? And how can they do science (the process) without any content as background? With little direct teacher “control,” why did classes not simply descend into anarchy? How did teachers keep the classes moving in a productive direction if the students were in control? Why and how are Exeter students so successful at teaching themselves, when this approach seems like it would be a major challenge at Lakeside? Just a couple of classroom observations largely answered these questions for me.

Without lecture, how do students learn any content?

Just because students do not listen to lecture does not mean that they don’t receive any sort of direct instruction or learn any facts – the direct instruction just doesn’t come from the teacher. Part of the Harkness method relies on students learning much of the factual content of the unit outside of class, often from a text book or other reading assignment. Class time is often reserved for applications of concepts, lab investigations, problem solving, and extensions or elaborations of basic material. In some ways this is the opposite of the approach we take at Lakeside, in which basic content is often explained (by the teacher) during class, and homework is used as time to practice problem solving and look at extensions or applications of the basic material. Exeter students reported that they really liked and appreciated their approach: “I can learn all the basic stuff on my own in the dorm,” one student told us. “I like the idea that we spend class time doing the harder and more complicated stuff together. I would find it really difficult if we learned the basic stuff in class and I had to do the hard stuff on my own for homework. It’s much easier with many brains.”

Sometimes, the students have a hard time understanding all of the material at home. When this happens, they bring in questions to the class. “I didn’t get why the second Ka didn’t matter in this acid/base problem,” one student remarked. The teacher said nothing, but another student jumped right in: “See how the second Ka is way, way smaller than this one? Like five orders of magnitude. It’s a terrible acid, so that second H+ just doesn’t ionize hardly at all.” Sometimes questions came up (from a student or the teacher) that no one seemed to know the answer to. In that case, students pounce on their text books (which are always brought to class and usually open on the table) and look up the answer. Because students are accustomed to taking responsibility for their own learning, they have become experts at “how to find the answer” for themselves. Unlike Lakesiders, their reference of first resort (during class) is almost always a book and not the internet. Also, they rarely ask their teachers for the answer to a question, and when they do, they don’t necessarily expect a direct answer. Often, instead, they ask the question to the classroom at large, and another student (or two or three!) will respond. Teachers do feel free to chime in on occasion when they feel their input will be particularly helpful. I also noticed that they sometimes do deliberate check-ins with students who had questions or concerns about the concepts – “Jonathan, are you OK with that now?”

Content is not always learned just at home. Sometimes concepts and ideas are actually developed during class itself through a kind of discovery learning. I watched a physics class in which the teacher posed a question: “What kind of variables affect the speed of a wave?” He was seated with the rest of class around the Harkness table, and was taking notes on a tablet PC. A data projector showed his notes on a large screen. Instead of generating his own notes for the students to copy down, the teacher simply transcribed the student discussion that transpired, serving as a kind of scribe or recording secretary for the lesson. He wrote down student observations and questions, and carefully drew a line through student hypotheses that were later determined to be incorrect (by the students). The physics teacher provided a simple wave machine demo device for the students to experiment with, along with some physical springs and slinkies that could make various kinds of waves. He also used physics software on his tablet PC that he manipulated at the request and direction of the students. The students used these devices and demos to experiment with different hypotheses: Did changing the amplitude of the wave change its speed? How about changing its frequency or wavelength? Students played with the demos, asked each other questions, and drew pictures and graphs on the many whiteboards around the room. They were always very attentive and respectful of each other, and at all times there was only one conversation going at a time. In a few places where the students drew an incorrect conclusion, the teacher said nothing for several minutes, waiting to see if the students would catch their own error – usually they did. In one case, after 5 minutes passed, he stepped in to ask a pointed question, and the students realized their mistake. Near the end of the class, the students took a sharp right turn into a tangential question about the relationship between an amplitude vs. displacement graph of a wave and an amplitude vs. time representation of a wave. It was a subtle distinction – which kind of graph really showed the wave itself, and which showed only a certain position on the wave and how it changed over time – and what was the difference between the two? And the significance of these differences? I’m not sure if this discussion was really what the teacher had in mind for this particular class, but it was a fascinating conversation that the students seemed to get a lot out of, and the teacher allowed it to basically run its course. At the end of the lesson, the teacher had recorded a neat outline of the entire lesson, and emailed this to the class – another strange inversion (the students present the material and the teacher takes the notes!).

Many chemistry classes were not too different from ones I have observed at Lakeside. Many of them centered around student problem solving, either debriefing homework assignments or working on application or extension problems. In almost all cases, students worked in groups of two or three. Sometimes these groups were assigned by the teacher; in other cases, students simply worked with the people seated near them. It was rare that students were asked to complete any task in class by themselves without the possibility of help or collaboration from a peer. In a couple cases, students performed a lab or a lab-like investigation, even during a “short” 50- minute period. The teachers reported that often they will start a unit with a lab (Exeter chemistry classes do 1-2 labs a week), and use this experience to introduce the material to the students. This gives students some introductory information, and also a ready-made source of questions for further investigation.

A Chemistry Classroom with both Harkness Table and Lab Space

With little direct teacher “control,” why did classes not simply descend into anarchy? How did teachers keep the classes moving in a productive direction if the students were in control?

On the surface, it appears that the students have significant control over the class. But this appearance of total student direction and control is somewhat of an illusion. Upon further investigation, it is revealed that every lesson is carefully crafted and planned by the teacher. He or she does not simply walk into the classroom and say, “learn chemistry!” In fact, each day is mapped out ahead of time. In many cases handouts are prepared to guide the kids, or a slate of questions is written up ahead of time. Examples are picked very carefully to illustrate key points, and labs and demos are chosen to guide students in the right direction. While it sometimes feels to the students as if they are bushwhacking their way through some unexplored jungle, they are in fact traversing a definite path with subtle signposts and markers along the way. If the students wander astray from the main track, the teacher gently (or sharply) reins them in and points them back down a more productive direction. The challenge for the teacher is to provide just the right amount of guidance and scaffolding so that the students can achieve progress on their own without it seeming either too easy or too onerous. Despite the basic premise that the class is student-centered, teachers are not afraid to be remarkably direct and involved on occasion: “Let’s hold off on that line of thinking for now.” “I’m afraid I don’t agree.” “I think we can skip X for now and just focus on Y for the moment.” “Take 5 minutes right now and summarize this discussion in your notes.”

One interesting consequence of the fact that the students have significant control over the classroom is that the pace of each class seems relaxed, almost leisurely. In observing many 45-minute classes at Lakeside, there is often a sense of urgency or even stridency, especially in the last 10 minutes or so of the period. The teacher is rushing to finish his point, or to get to her demo, or to solve that one last problem. In the “rush to finish” the lesson, important points are sometimes overlooked. In fact, many Lakeside teachers and students remark that the Weds-Thurs block periods often feel much more relaxed because there isn’t as much time pressure to “squeeze everything in.” At Exeter, many of the short periods feel as relaxed and unrushed as Lakeside’s block periods. Because the students control much of the tempo and pacing, they move at a speed that is comfortable to them. They have no particular incentive to “get through one more example” or “cover 3 more points” in the last 10 minutes of class. If they need more time to understand something, they take it. If they are ready to move on, they will. This slower pacing no doubt contributes to less material being covered each week, but it certainly makes for a less stressful class period.

We noticed that the relaxed feeling carried over into the field trip as well. On Lakeside field trips, we often expect students to take notes, do field sketches, etc. On the Exeter Ornithology field trip, students were encouraged to soak in the experience and focus on observing the wildlife around them. The teacher took notes, and provided the students with a summary of the species observed when the trip was finished.

Another interesting observation relating to pacing is the effect on the classroom when the teacher sits down with the students. While a teacher who is physically active walking around the room has the potential to create some dynamic energy, he or she also is potentially giving students permission to be passive observers of the “show.” When the teacher sits with the students, there is less kinesthetic action, but somehow there is also the expectation of intimate, reciprocal conversation. While it’s not necessarily strange or rude to remain silent during a lecture (even when questions are being asked), it IS uncomfortable when one party refuses to participate in a personal conversation. Sitting at the Harkness table brings the whole class into “conversation mode” and out of the “lecture” setting.

Why and how are Exeter students so successful at teaching themselves, when this approach seems like it would be a major challenge at Lakeside?

The biggest difference here seems to be the school culture and the training that Exeter students receive. They come to the school knowing that the Harkness method will be used extensively, and they practice it every day in every one of their classes. The idea that students should be responsible for their own learning becomes deeply ingrained in the school culture. Students don’t struggle with this responsibility (at least not in upper level courses) because they are completely comfortable and practiced with this approach. Lakesiders certainly could get to be comfortable with a system like this (in fact a number of teachers here use variants of it), but they would need to be trained to use it in the science context. It certainly wouldn’t be an easy or seamless shift in approach for our students or our teachers.

Other differences between Exeter and Lakeside involve average course loads and class sizes. Exeter is on the trimester system (which they call “terms”). The maximum number of courses that any student can take per term is five (although music lessons can be taken in addition to their normal course load). Most core science classes (i.e. biology, chemistry, physics) meet all three terms during the year, while elective science classes (i.e. Marine Biology, Astronomy) meet only one. There is also supervised and structured study time throughout the day (and evening). All of these things combined with the fact that very few students spend time each day commuting to and from school (80% of the kids are boarding) mean that students have more time on average to prepare for each lesson outside of class. Class sizes are also smaller than Lakeside, with an average class being about 10-12. Classes as small as 8 are not uncommon, and there is a hard cap at 14. Smaller classes give each student more of a chance to participate in each lesson.

Technology and Harkness

While technology does not relate directly to the Harkness approach, it was interesting to see how technology was used (and not used) in the Exeter science classrooms. In all of our observations, we only saw a single student use a laptop during class. While almost all students have computers, they are discouraged from using them during the normal class lessons. One teacher explained that the heart of the Harkness philosophy is that students sit in a circle and communicate directly to each other. The laptop becomes a distraction – if students are busy looking at their screens then they are not looking at one another. This is an interesting contrast to the widespread use of laptops at Lakeside. Here laptops are employed very effectively as a teaching and learning tool in many classes, but they also are a source of distraction and disengagement for many students.

Exeter has also essentially rejected the SMART board and related technologies. While the teachers there were intrigued by some of its possibilities, they decided that ultimately it is an embodiment of a teacher-centered classroom (or at the very least a technology that is primarily designed to be used by one person at a time, and not by a group).

Tablet PCs were used on several occasions by the teacher to record notes for the class, or to project demos, simulations, movies, or web pages on the big screen in each classroom. These seemed to be popular and well utilized. Interestingly, each classroom has a dedicated tablet PC just for use with the projector – this is NOT the teacher’s personal [work] computer. Most teachers have a desktop computer for their personal use in the classroom. Each teacher essentially has his or her own room, so there are not group offices for the full time faculty.

Harkness as a “Flipped Classroom” Model?

In many ways, the Harkness Method is a lot like the “flipped” model of classroom instruction, in which students learn basic content at home and practice skills and do applications during class. A major difference is that the “flipped” model is often associated with watching videos or seeing online audio-visual presentations. At Exeter, students usually get the content by reading books and articles. Caryn and I joked that Harkness is like a 19th Century version of the flipped classroom. Except in this case, I’m not sure the technological progress of the 21st Century is entirely serving the students. While the video format certainly opens the doors to some powerful visuals and demonstrations, it comes at the expense of time spent reading and digesting the written word. Am I old-fashioned to think that by essentially jettisoning books and relying on pre-digested mini-videos (akin to “watching TV”?), the modern flipped model is robbing students of a very important set of skills?

Relation of Harkness to Other Educational Philosophies

At first glance the Harkness method, particularly as adopted by the science department, seems to share a lot in common with the progressive educational psychology theories of the late 20th and early 21st Centuries. Watching a science lesson at Exeter, you could easily imagine that it was recently designed by an educational psychologist from a well-known college of education. The inquiry or discovery methods that grew out of earlier work by Piaget and his intellectual descendants stress student-centered lessons featuring constructivism, the idea that students can and should create their own meaning and knowledge through being actively engaged with the world around them. Under the constructivist model, teachers act like a guide or mentor, not the source for all information. The constructivist/inquiry model of science education is now the standard approach taught at most American teacher colleges.

While the Harkness method seems to share many similarities with the constructivist/inquiry model, it is a distinct phenomenon that in fact does not seem to draw much direct inspiration from the academic world of educational psychology. Most of the teachers I spoke to did not know much about these theories or have any sort of formal or informal training in educational psychology. Relatively few Exeter science teachers appear to have attended teachers’ college or studied current writings in cognitive psychology or current science education philosophy. In contrast, they came to learn about the student-centered classroom by watching other Exeter teachers practice their craft. In this way it is very much like an apprenticeship system in which young teachers are trained by the experienced masters by direct observation and instruction. In hiring new science faculty, the department looks for teachers who are open to the idea of a student-centered classroom, but not necessarily those who have extensive experience or training in this approach. Exeter provides the training and mentorship needed to help teachers new to the school adopt the Harkness approach.

As someone who has been through the UW’s College of Education, the Exeter experience was a little jarring. I would watch 40 minutes of an incredibly elegant student-driven constructivist lesson. Then the teacher would hand out a chemistry lab with step-by-step cookbook instructions, which did not seem in keeping with the constructivist approach. Or the students would take a quiz which was entirely multiple choice or fill-in-the-blank, a seemingly odd choice for a chemistry or physics class. The pairing of very traditional education methods in assessment and laboratory work with a total student-centered inquiry/discovery class discussion seemed a bit incongruous, although it’s hard to draw too many firm conclusions on the basis of such a limited observation.

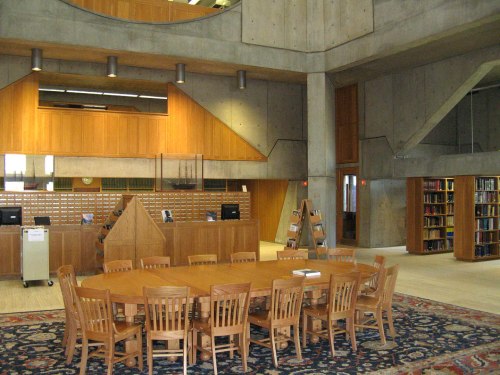

Library Lobby with Harkness Table

New Teacher Evaluation and Induction

As mentioned above, Exeter science teachers are not required to have specific background or training in the Harkness style before they are hired. Instead they look for teachers with a lot of potential to be successful in this environment, and an openness and willingness to use Harkness methodology. Essentially, it sounds like they usually “grow their own teachers.”

Every teacher new to Exeter gets a mentor who works closely with that new teacher. In contrast to the Lakeside system, the mentor is always from the science department (and almost always from the same subdepartment – a fellow physics teacher, for example). At Exeter there are three terms (trimesters) a year, and new teachers are evaluated for NINE terms in a row. Evaluations happen in their 2nd, 3rd, 4th, etc. up through 10th term. This means twice in their first year, three times in their second year, three times in their third year, and once in their fourth year. The fourth year serves as the summative evaluation year for that teacher, when a decision is made about whether or not to offer the teacher tenure. Tenured teachers are invited back for a fifth year and have the expectation of job security for that year and every subsequent year. Teachers who don’t receive tenure are not invited back after the fourth year.

Each evaluation is performed by a tenured teacher in the department (but not necessarily the department head). For each evaluation, the tenured teacher sits in on 3 classes in a row, observing the lessons and meeting with the teacher after each class. The new teacher and the tenured one have some substantive discussions together, and a document is written which summarizes the visits. While these nine evaluations contribute to the overall summative assessment in year four, individually they are largely formative evaluations designed to give constructive feedback to the teacher and aid in his or her growth and development. By the end of the evaluation process, a new teacher will have had at least 27 official class observations and 27 one-on-one meetings with up to nine different people to talk about the teaching and learning happening in the new teacher’s classroom. It is not uncommon for new Exeter teachers to also sit in on their colleagues’ classes every day for their first year or two on campus.

Compared to the Lakeside system of having two official evaluations in the first four years (plus some mentor visits in the first year), the Exeter process is an incredibly intensive. Their focus is really on developing new hires into Harkness master teachers. This evaluation system also provides some significant professional development for the tenured teachers in the department, because there is an expectation that each of them will help with the evaluation process. Currently the Exeter science department has 17 tenured teachers and 3 new teachers (in their first four years), which means that each tenured teacher does an evaluation on average every couple of years.

In the past, tenured teachers were not subject to any additional evaluations of their own. The Exeter faculty are in the process of adding an additional formative evaluation system for tenured teachers.

Weekly Meditation Period

Students and faculty/staff meet once a week for a 30 minute “Meditation” period (Thursdays from 9:50-10:20am). Meditation takes place in the school chapel (Phillips Church). It is an optional event, although the day we attended the chapel was packed with several hundred attendees. Typically meditation involves some music and quiet time, and also a speech or presentation by a member of the community. During the fall and winter terms, the meditation is given by a teacher or staff member. In the spring term, students give all of the meditations. The format and content of the talk is pretty open, with presentations on ideas, beliefs, philosophies, interests, hobbies, etc.

Phillips Church

The meditation that we attended was given by a senior student recounting her tremendous struggles with anorexia and other eating disorders. Her narrative was compelling and almost poetic, and the audience was totally absorbed, hanging on her every word. The experience was a powerful one for all involved. Apparently all students practice writing a meditation in the winter of their senior year, and then a select number of them are chosen to actually present their meditation to the school. Even though attendance is not required, many adults and students spoke very highly of this weekly event and said that they make a point to attend every time. Meditation seems to be a powerful way that community is built and maintained at Exeter.

My trip to Exeter was enlightening, and inspired me to really think about “what good teaching is.” Although Exeter is obviously a place of incredible financial resources, the fundamental ideas and philosophy of the Harkness method do not require expensive facilities or equipment. But they do require a willingness to re-center the teacher-student balance within the classroom.

Thank you for sharing this wonderful, inspiring article. As an educator I am very intrigued by the Harkness method and how it seems to allow kids to realize that they are capable of learning and seeking out knowledge on their own, rather than expecting to be spoon fed during lecture based lessons.

Pingback: What I Learned From a Year of Visiting Schools | Periodic Wanderings

This was such an inspiring entry. What a wonderful opportunity this school provides.