I spent the last five days first driving down the mainline Florida Keys and then travelling by ship to the Dry Tortugas, a set of low-lying islets about 70 miles off the coast of Key West.

Just traveling to Key West is a remarkable journey. It is about three hours south of Miami on US 1, also known as the Overseas Highway. The name is apt, as you can often see the Gulf of Mexico to your right and the Atlantic on your left as you traverse this relatively narrow two-lane highway. The most impressive stretch is Seven Mile Bridge, a span that covers almost seven miles of open water between Knight’s Key and Little Duck Key.

The Keys hold a remarkable diversity of special wildlife. I saw the endemic Key Deer, a miniature race of White-tailed Deer. They stand about two feet tall at the shoulder, making them a little larger than a cocker spaniel. There were also plenty of cool birds, including a rare Western Spindalis, Mangrove Cuckoo, Black-whiskered Vireo, and the majestic Magnificent Frigatebird:

Frigatebirds are kleptoparasites, meaning that they steal food from other birds. They will wait until a smaller seabird like a gull or tern has captured a fish, and then harass it until it drops its prey.

I didn’t get too many photos of the mainline Keys because the weather was incredibly stormy. Thursday was particularly crazy, when 4.14 inches of rain fell in the span of about four hours. It was the fifth wettest May day ever recorded in Key West, and many of the streets were flooded by up to 18 inches of water. As a reference for you Seattle folks, we only have three months where our average monthly precipitation is more than 4.14 inches (November through January).

On Friday, I joined Wes Biggs and Florida Nature Tours aboard the M/V Spree for a three day tour of the Dry Tortugas.

Wes is an extremely experienced and knowledgeable birder, and a real character. He has a story for every occasion, and an opinion on pretty much every topic. I really enjoyed getting to know him a bit on this trip.

It took about seven hours to motor out to the Dry Tortugas, about 70 miles west of our marina on Stock Island. The Tortugas were first discovered by Europeans by Juan Ponce de Leon in 1513 as he explored the lands that were to become Florida. He named them Las Tortugas because his men collected many sea turtles there for food; the adjective ‘dry’ was added later on nautical charts to indicate that they are too small and too low to provide any fresh water. The three largest islands in the group are between 30 and 60 acres, with three or four other much smaller islets. They sit just a couple feet above sea level.

In 1846, the Federal Government began to build a fort on Garden Key, a construction project that continued for decades. Fort Jefferson was never really finished, but it is an impressive edifice:

It takes up more than 90% of the land area of Garden Key, and with 16 million bricks is the largest masonry structure in all of the Americas. It was an active military base through most of the 19th Century, and was an important Union outpost during the Civil War.

Most famously, Fort Jefferson was where Dr. Samuel Mudd was imprisoned for a number of years after he was convicted of conspiring to kill Abraham Lincoln. Mudd treated John Wilkes Booth’s broken leg after he assassinated Lincoln, and was alleged to have been involved in a plot to kidnap the president.

Some claim that Dr. Mudd is the original inspiration for the expression “your name is mud(d)” – although this is disputed. After he tried to escape, Mudd was sent to live in the dungeon:

Over time, his reputation changed somewhat. Dr. Mudd was present during a yellow fever outbreak in the late 1860s, and helped to treat the many affected prisoners and soldiers. He was eventually pardoned for his great medical efforts in 1869.

Today, Fort Jefferson is the heart of Dry Tortugas National Park, and one of the places we spent the most time on our three day trip.

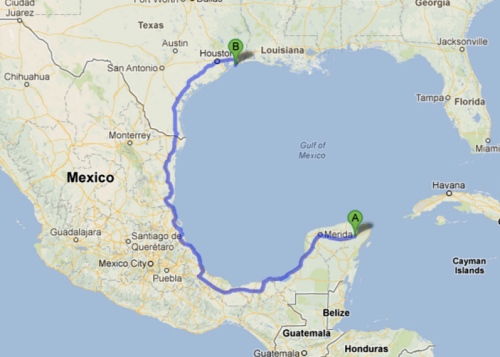

The interior of the fort is filled with grass, trees, and bushes – the perfect stop-over point for trans-Gulf migrants on their way from the Yucatan or the Caribbean to the US mainland.

We saw a number of warblers, thrushes, vireos, and flycatchers who dropped in for a rest and a bite to eat, including this gorgeous Scarlet Tanager.

In addition to searching for passerines on Garden Key, seabirds were another focus of the trip. One of my favorite is the large tropical tern called a Brown Noddy:

We saw thousands of Brown Noddies and Sooty Terns nesting on Bush Key:

Hey, someone needs to tell all those birds that this island is closed!

We also saw both Brown and Masked Boobies. Hospital Key, not much more than a big sand bar, is the only nesting site for Masked Booby in the United States. This Key was named during the yellow fever outbreak, when it served as a quarantine area.

Those tiny white dots are the Masked Boobies. A pod of dolphins also greeted us upon our arrival at Hospital Key:

We also visited Loggerhead Key, the largest of the Tortugas islands and the home to the Loggerhead lighthouse.

After three amazing days, it was time to head back to Key West. The seas were a bit rougher than normal, and despite the many wonders I had witnessed I was ready to spend the night on dry land. The Tortugas are a special place, and I hope to return some day with my kids to share its magic with them.