I visited my friend Bill at SHS again last week. You might remember him from this post from November in which I described the STEM program he helped to start. As part of the STEM initiative, students investigate real-world problems and use literature and laboratory research to try to uncover real-world answers to these problems. Over the past few weeks they have been studying cancer, and one question that they have been trying to answer is “How can chemotherapy treatment single out just cancerous cells in the body while leaving healthy cells alone?”

This topic has the potential to grab students right away. Even 9th graders usually know someone touched by cancer: a friend, relative, or neighbor. And the question is a subtle and complex one. Basic chemotherapy usually involves introducing a cytotoxin (a chemical that damages or kills cells) into the body. Because cancer cells grow much more rapidly than most other cells, they are more affected by the cytotoxin than normal cells and (in the best case scenarios) the cancer cells die while the normal cells survive. Unfortunately in most cases healthy cells are also affected by chemo, especially those that grow and divide rapidly – like cells that make skin and hair (which is why chemo can cause hair loss). An ideal treatment would target ONLY cancerous cells, and leave healthy cells alone. This is the kind of treatment that Bill’s students began to investigate.

Bill and his kids got some important help from Dr. A.J. Boydston, a Chemistry Professor at the University of Washington. Among many other things, Dr. Boydston studies polymers which can form micelles – large molecules that can aggregate together to form a kind of cage. The idea is that you could build a custom molecular cage to hold, for example, a cytotoxic chemotherapy drug. Then you could inject the caged drug into the patient. As long as the drug is trapped inside the cage, it won’t harm any cells. The key is to build a cage that remains closed as it bumps into normal cells, but springs open if it encounters a cancerous one to release the drug and kill the cell.

But how can you build a molecular cage that can remain ‘sealed’ for period of time, and then spring open? And how can it tell a cancerous cell from a healthy one? These are questions that Bill and his students explored, with the help of Dr. Boydston. It turns out that if you vary the building blocks (monomers) of the polymers, you can change the properties of the micelle cages that are formed. Some polymers will create cages that open in the presence of acid or base. Some will open when exposed to ultraviolet light or ultrasonic agitation. The students set out to design and create different polymers using different monomer building blocks.

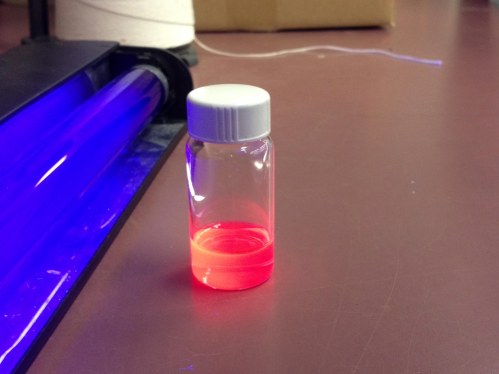

The Boydston Lab provided the actual, synthesized polymers – the same ones that they are using for their professional research. Then the students began testing the different polymer cages to see under what circumstances they remained closed, and when they opened to release their contents. Instead of using actual poisonous cytotoxins, the students used a dye called Nile Red to simulate the behavior of a chemotherapy drug. Nile Red fluoresces under the action of UV light when trapped inside the micelle, but it does not when it is released into an aqueous environment. Thus the students could use UV light to see if the “drug” was successfully trapped in the micelle, and when it came out.

Various student groups tested different conditions to see exactly when the micelles opened and when they did not. Medical research on actual tumors indicates that many of them are more acidic that normal tissue by as much as 1 pH unit (a factor of 10 in acid concentration!), so polymer micelles that open in acid might be promising. Doctors and researches are also experimenting with next-generation powerful light sources. Micelles that open when exposed to a certain frequency of light could be useful if doctors can pin-point particular cancerous areas and illuminate them appropriately.

While Bill and A.J. were on hand to answer questions and supervise the experiments, I was impressed with how the students took responsibility for their own investigations. They had to really think about what they should do at each step in the lab, and what the results meant for their particular polymer. At the end of the experiment, the students had to write up their research in the form of an academic poster, a format familiar to real scientists, professors, and grad students.

This was a super-ambitious project for 9th graders, and I was impressed with how well Bill, A.J., and their colleagues pulled it off. It was exciting for the students to work with actual research equipment and actual research polymers that may be approved for therapeutic use in humans within this decade. They dug deeply into the concept of experimental design, and had to understand a host of complicated chemical concepts from acid/base chemistry to intermolecular forces, and to use those ideas in concert. While some of the more detailed intricacies of the science were a bit beyond the comprehension of these 9th graders, the basic principles were well within their grasp – as was the realization that science can be a powerful tool for good, and that they are capable of using that tool themselves.